The Hero/Heroine’s Journey – Which Should You Follow?

The Hero’s Journey has been popularized for years now, with many books and writers using it as a framework for creating and analyzing stories. The Heroine’s Journey is less well known, but offers an important alternative to the aggressive, individualistic stories that populate the hero’s universe. Understanding both can give your story deeper resonance and connect with our primal human storytelling instincts, drawing readers in despite themselves.

Both are based on myths that are thousands of years old, and that tap into a reader’s psyche in deep ways. Even if a reader doesn’t know they are reading a story based on one of these monomyths, they instinctively know when it’s following the expected progression (or not).

First off, I want to be clear that in talking about the Hero/Heroine’s Journeys, we are not talking about inherent sex/gender constructs. A Hero on the Hero’s Journey can be male or female, and a Heroine on the Heroine’s Journey can be female or male (or indeed, anything in between, for either). The distinction has to do with the underlying structure of the story, and how the Hero/ine engages with it.

Basic Hero’s Journey

image ©Unknown (Wikipedia)

The major story beats are:

Call to adventure – Hero is pulled toward his Quest

Withdrawal (Quest) - Hero must abandon his community to seek his destiny

Visits the Underworld, defeats the enemy (one on one), receives a boon/reward

The Return with the Elixir – Hero is acknowledged as a Hero

There are frequent withdrawals/returns as the hero meets dangers and obstacles in the form of situations or people that oppose his quest.

The focus is on:

An increase in self-reliance and personal strength; the Hero may have helpers but eventually he must go it alone to defeat the Villain. Hero often ends up alone at the end.

The Hero must often sacrifice what s/he loves – or even him/herself.

Motive for the quest is often revenge or total defeat of the enemy.

Examples: Star Wars, Wonder Woman, Game of Thrones, Jack Reacher and similar novels; most thrillers/action-adventure stories.

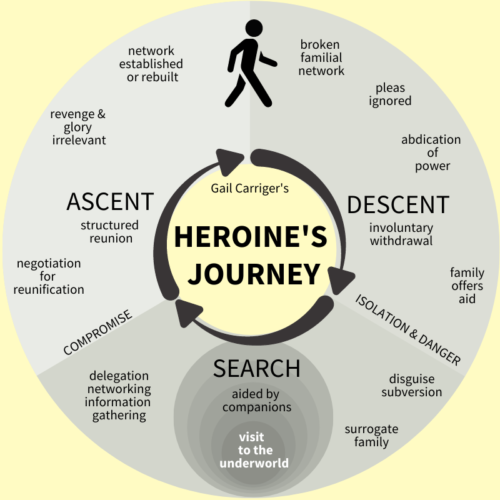

Basic Heroine’s Journey

image ©Gail Carriger

The major story beats are:

The Descent (initial loss or separation that forces the Heroine to confront a loss of family/community, resulting in isolation)

The Search – seeking re-union

The Descent to the Underworld – friends/family aid her in achieving her quest

Ascent – based on negotiation, compromise; reunion of family or network

The focus is on:

Balance, compromise, team-building, relationships, connection - strength in community

Asking for help and giving help to others

Defensive vs. offensive strategies

Heroine is often responsible for delegating to her team and helping others fulfill their own promise.

Heroine is restored to or even enhanced in her place in her community.

Examples: The Harry Potter series; the Twilight series; romance novels, cozy mysteries

Note that these are just the bare bones of these two Journeys. For full explanations of both of these, you should read the following, which give many fleshed-out examples of these journeys from popular books and films.

The Hero’s Journey – Christopher Vogler

The Heroine’s Journey – Gail Carriger (note: there are also Heroine’s Journey maps based on Maureen Murdock’s work, wherein the Heroine identifies with the masculine to start, then through trials and accumulation of knowledge, learns to identify with the feminine. That requires a more nuanced explanation than I have room for here, but if you do a web search for it, it will come up and may resonate with you.)

Strengths of this approach:

Stories based on these monomyths tap into deep psychic storytelling roots. Our brains respond to stories based on these frameworks because they come from myths that are thousands of years old – stories people have responded to since storytelling began.

They are more complex than the structures we looked at last week, giving a broader canvas to work with and mor options for plot and character development.

Challenges of this approach:

Both are still more plot-focused. Character sketches here are broad, following the myth rather than developing characters deeply.

If not used carefully they can also create rather formulaic stories, similar to many we’ve seen before. Note that you don’t have to follow the exact steps in every story, or even in the order they’re presented. Making it fresh with new twists is crucial – but you also need to keep the recognizable chassis of whichever monomyth you’re using. If you try to mix them, readers may get frustrated.

Which Journey are you drawn to in your writing? If you’ve grown up only focused on the Hero’s Journey, but it doesn’t feel quite right for your story, you may feel more comfortable with the Heroine’s Journey. Looking at your current work in progress, which would you say might serve your story better?