Cause-and-Effect Structure: Story Genius and the Inside Outline

This week we’re going to take a look at two other methods of dealing with plot and structure, courtesy of Lisa Cron and Jennie Nash. Both of these focus on developing a cause-and-effect trajectory that meshes the character arc with the action plot, so the character growth and transformation happen as a result of what happens in the story. They differ in the way they structure their story “blueprints” but I know writers who swear by each (and I use them as well).

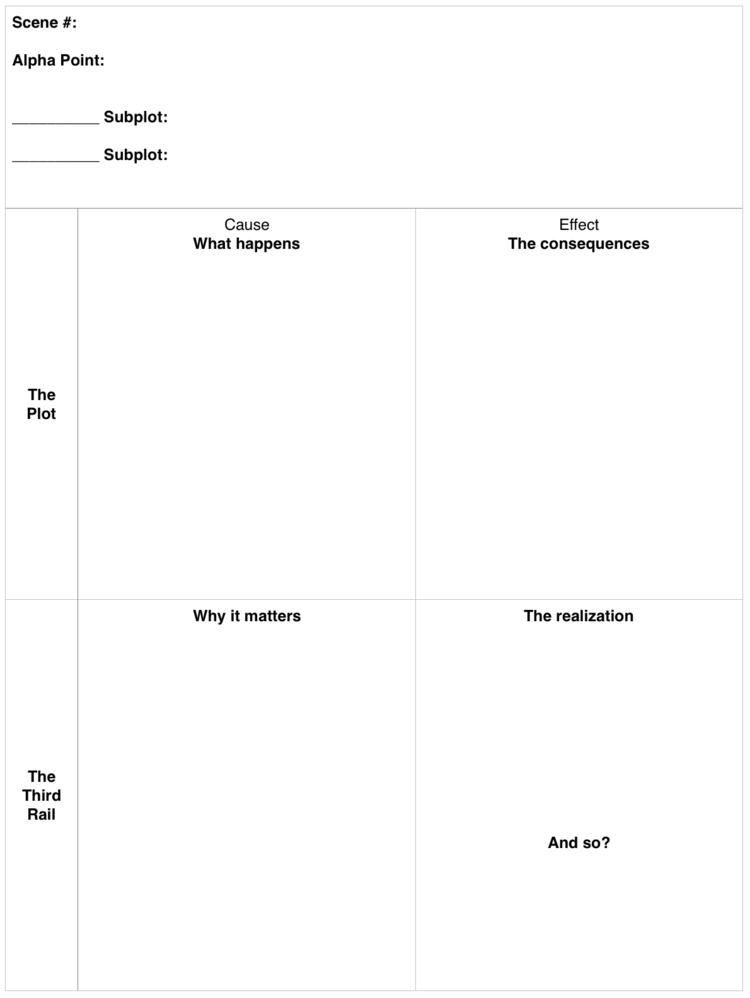

Lisa Cron, in Story Genius, advocates building scenes using Scene Cards, as shown here:

Image by Lisa Cron, from Story Genius

Scene # - 1, 2, 3, etc.

Alpha Point: This is the main point of the scene. Why is it necessary? Note a scene may have several points, and move along the main plot as well as several subplots (see below)

Subplot(s): If this scene is part of a subplot, which one?

The Plot – Cause: What happens in the scene.

The Plot – Effect: The consequence

The Third Rail – Why it matters to the character, and the realization that happens as a result; leads to the question, “And so?” which leads to the next scene.

Note that The Plot focuses on the external action, and The Third Rail is all about internal character development.

Every scene must feature a change, internal and external. These don’t have to be Big Life-Altering Changes; a call, a decision, a realization, a new plan, a setback... this makes sure your story moves forward with each scene.

However, every “what happens” may have multiple reasons why it matters, or many possible consequences or realizations that may come from it. This is why it is a good idea to draft out scene cards for at least the major scenes of your novel before you start. You can always fill in details or make changes later. You can play with the cards until you find a storyline that feels right.

Of course, you have to keep your eye on the real problem your main character faces – the flaw she has to overcome, and the change she has to go through by the end. What happens has to flow out of the character development, not the other way around. It is easy to fall in love with a story only to realize it has nothing to do with the character’s real issues.

That’s the basic idea behind Scene Cards. You write one for every scene in your novel, even the ones that seem small or completely obvious, so that you know each scene makes sense and has earned its place.

Jennie Nash’s Inside Outline method, described in her book, Blueprint for a Book: Build Your Novel from the Inside Out, is similar in that it helps you develop a cause-and-effect trajectory to keep your story moving forward in a way that combines character and plot development (and as with Story genius, ensures character drives plot development).

The Blueprint is actually a multi-step process that begins even before you write the cause-and-effect Inside Outline. It asks questions to help you frame your story, such as identifying your ideal reader, writing your back jacket copy, and defining the point of the book – why you’re writing it in the first place.

Then we get to the Inside Outline, a simple structure that charts your scenes. No grid to fill in here, just two lines with one or two sentences each:

Scene: what happens (action plot)

Point: what it means for the character, and how they react – what decision, or action they take as a result (character development/emotional plot)

Because of that... leads to the next scene

Easy, right? Yes and no. It’s easy to tell what happens in a scene, but if you’re not careful, you can fall into the trap of having the character always reacting to what is happening, instead of driving the action forward. So that last line is important. Because of that... is specifically about what action or decision the character takes that leads to the next thing that happens.

Jennie’s hard and fast rule is to make the initial Inside Outline no more than three pages. This means not every single scene will make it in, but the major ones will. Again, this is helpful to do before you write so you know you’re not writing yourself into a corner. You can add or change these as you go, to make sure you’re still heading in a direction that makes sense.

If you do it at the end of a draft, it helps you make sure that every scene is working toward the cause-and-effect trajectory. A great way to get rid of unneeded scenes, or combine them with more robust ones.

It is helpful to write it in multiple colors to denote different subplots or point-of-view characters.

This system also allows you a quick way to check possible ideas for how the story should go, before writing too far forward. If it’s not going to work, better to waste a few pages of an Inside Outline than pages of writing.

Strengths of these approaches:

The focus on developing a cause-and-effect trajectory means character develops entwined with the novel’s plot. It’s hard to shoehorn in a plot device or character transformation with no setup if you do it right.

Flexible blueprint that can change as you write. Can also be used after a first draft to see if you really do have a cause-and-effect trajectory, or if you have too many random scenes, lack character transformation, etc.

Can be combined with other structural approaches. You can still have an Inciting Incident, Plot Turning Points, Midpoint, Crisis, etc. It’s easier to make sure you get there organically instead of forcing your characters through the plot like rats in a maze.

Quick way to think about your story’s development before your write fifty pages that go nowhere.

Challenges of these approaches:

It may take some time to learn the approach and do it well. People often want to rush through the process, and think they’ve done a cause-and-effect trajectory, but it’s still based on what they want to have happen, vs. what should happen naturally as a result of previous scenes. This is especially true if you already have a draft (or something you consider “almost done”). The temptation is to make the blueprint fit the story, and ignore any messy spots. You have to be willing to be honest, and make radical changes if it becomes apparent they’re necessary.

“Pantsers” or discovery writers still get nervous because they believe it puts them in a straightjacket – once they start using the blueprint, they’ll be forced to follow it. Not so! You can always change the blueprint, but again, you need to be honest about where changes are needed. In fact, it may help since you can build as you go, just making sure each scene springs organically from the previous one. In yes, a cause-and-effect trajectory.

You have to think deeply about your scenes, and how to put them together. Again, I’ve had clients that glossed over this process, and didn’t want to do the real work involved. If you do, however, you’ll have a story that works on both the plot and character levels.