Let’s Talk About Story Structure: The Basics

Ever since Aristotle came up with his three-act structure, writers have been trying to refine it to suit their stories. This month, we’re going to take a deep dive into plot and structure, and look at several popular ways writers have expanded on the topic of “how to structure your story.” We’ll look at the pros and cons, or strengths and weaknesses, of each approach. I won’t get to every possible one out there, but these should at least give you some new tools for your toolbox, and a glimpse of different ways to approach your story.

First, know that these are not meant to be prescriptive, paint-by-numbers models. You may even combine several approaches. You may mix up the steps. Use these as building blocks, or a story chassis, if they make sense to you.

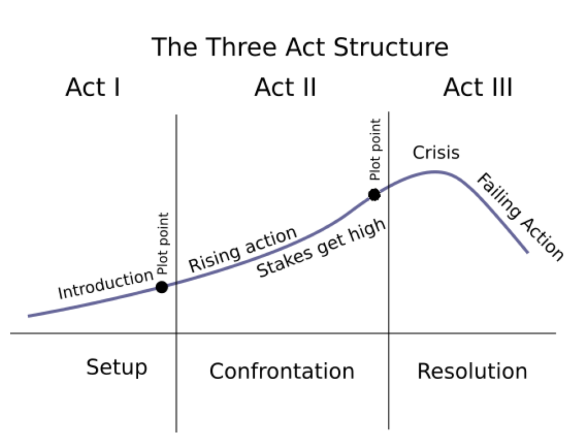

The original 3 Act Structure looks something like this:

Image from Arc Studio

Pretty basic, right? We’ve probably all seen it. Something happens that changes everything, then more stuff happens, increasing conflict until we reach a climax, then we fade off to the resolution. Fine as far as it goes, but it doesn’t give us much to go on in terms of actually telling a story.

One writer who has refined this is Larry Brooks, in his books Story Engineering and Story Physics.

He expands this to a 4 Part Structure:

As you can see, each part has its own specific beats, or milestones, that occur at fairly specific points in the narrative.

PART I – The Setup:

The Opening Scene, introducing your Protagonist and their world

The Hooking Moment, when we learn the Story Question that will need to be answered by the end

The Inciting Incident (unless this is your First Plot Point), the action, realization, or situation that changes the Protagonist’s life (whether or not they know it yet).

The First Plot Point shoves the protagonist into action, with tangible stakes and forces of opposition. In Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring, this happens when Gandalf arrives at Frodo’s cozy little hobbit-hole and tells him he has to scram out of town in secret, and take the ring with him, because some really bad guys called Ringwraiths are after him and they want the ring.

PART II – Response

Includes the First Pinch Point, which is “an example, or reminder, of the nature and implications of the antagonistic force.” (Story Engineering, p. 200).

The Midpoint is where new information enters the story that changes the context or understanding for your protagonist and/or the reader. It raises the stakes. What we thought the problem or goal was, is in fact very different.

PART III – Attack

The protagonist is no longer in response mode, but attack mode. The problem is now crystal clear, and the protagonist has to make a plan to attain the goal.

Includes the Second Pinch Point, is when we once again see the Antagonist in action, directly impacting the protagonist – a visceral reminder of what they are up against.

The Second Plot Point – When the Protagonist learns the final piece of the puzzle that will help him confront the Antagonist and defeat him. The all-is-lost moment often occurs right before this scene. Then, right on cue, the Protagonist gets a crucial piece of information or help that send them roaring toward the Climax.

PART IV – Resolution

This includes the plan to take down the Antagonist, all the way up to the Climax – the final showdown – and then the actual resolution of the story, in which the Protagonist deals with the aftermath of the Climax (this may be a happy-ever-after ending, or a neutral ending, or bittersweet, or even tragic, depending on the story you’re telling).

What I like about this approach:

It breaks the parts of story up into manageable pieces, even the “muddled middle.”

It tells you about where the milestones should occur (what % of your story). If you work it out in novels that seem particularly well-structured, they hit close to that mark

This gives you a loose guideline to follow – enough of an outline to make sure you have a comprehensive story but not so much that you feel shackled.

Possible drawbacks:

May seem formulaic

Doesn’t really address character development throughout the story. Much more of a focus on “what happens” rather than integrating character development. In fact, the novel he uses as his main example, Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code, is an example of an action-forward book where the characters do not grow and change over the course of the novel.

Overall, this basic story structure has a lot to recommend it, especially if how a compelling story actually goes together is a mystery to you. It’s a form, not a formula, giving you lots of leeway as to how you tell your story, and works for pretty much any type of story.

Next week, we’ll tackle the Hero and Heroine’s Journeys.